What Makes a Good Life?

Lessons from the Harvard Study of Adult Development

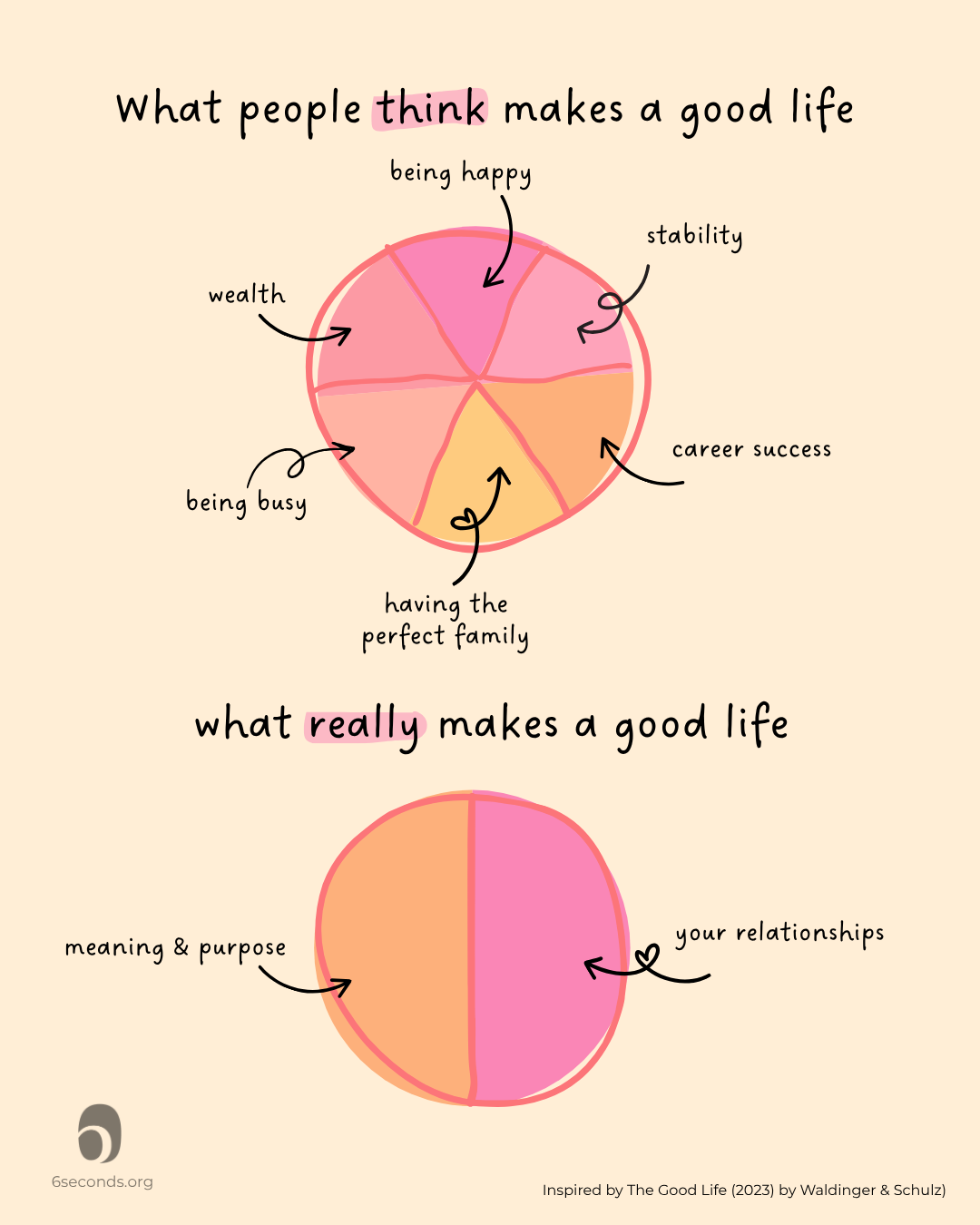

What if the key to a happy, healthy life wasn’t wealth, status, or IQ — but something far simpler and more profound: connection?

by Michael Miller and Alexandra Tanon Olsson

This is the powerful insight revealed by the Harvard Study of Adult Development, the longest-running research project on adult development in history. For over 85 years, researchers at Harvard have pursued a bold question: What makes a good life?

They enrolled hundreds of participants who agreed to a wide range of interviews, questionnaires, physical exams, and extensive health measurements. Despite numerous challenges, the study has continuously gathered data decade after decade — creating an unparalleled treasure trove of information about human wellbeing.

The study’s founder described its mission in 1942 as an effort to “help ease the disharmony of the world at large.” After nearly a century of research and analysis, what can these lives teach us? And how might these lessons help us all live better, more fulfilling lives?

3 Key Findings of the Harvard Study:

1. Success is seen over the arc of someone’s life, so think long-term

Joshua Shenk, a journalist from The Atlantic and one of the first non-researchers to look at the archives, said that “a glimpse of any one moment in a life can be deeply misleading.” Some participants who appeared well-adjusted and happy early on struggled with depression and loneliness later in life, while others with bleak prospects for success, ended up living long, meaningful, and satisfying lives.

So to answer the question of what makes a good life, it’s essential to look at the whole picture.

Take, for example, John Hines who seemed to shine throughout his childhood and his years at Harvard. The Grant Study staff noted the following: “Perhaps more than any other boy who has been in the Grant Study, the following participant exemplifies the qualities of a superior personality: stability, intelligence, good judgment, health, high purpose, and ideals.” But his life veered sharply. He married, took a job overseas, and struggled with substance abuse. He had an affair with a woman his therapist considered psychotic, and died in his 30s from a disease — despite his brilliance and privilege. He once reflected, “I think the most important element that has emerged in my own psychic picture is a fuller realization of my own hostilities. In early years I used to pride myself on not having any. This was probably because they were too deeply buried and I, unwilling and afraid to face them.”

Conversely, a man named Godfrey Minot Camille entered the Grant Study with the bleakest prospects for life satisfaction. He had the lowest predicted stability rating of all participants and had previously attempted suicide. His early years were marked by deep neglect — he ate meals alone until the age of six — and the pain and desolation followed him throughout his life. But at 35, he experienced what he described as a spiritual awakening. He became a psychiatrist, found a profound sense of purpose, and began using his pain as a tool to help others. By the end of his life, he was one of the happiest men in the study.

These are only a few examples of many that show how “a glimpse of any one moment in a life can be deeply misleading.” Success is seen from a wide perspective of an entire life, not from any particular moment or achievement.

But what’s the lesson we can learn from this?

The Grant Study — and the updated insights in The Good Life by current directors Dr. Robert Waldinger and Dr. Marc Schulz — emphasizes this long-term view: lifelong well-being is not determined by isolated events or achievements, but by how we continually grow, adapt, and stay connected to a sense of purpose over time.

34px

Thinking long-term: What will matter in five, ten, or twenty years? When we make choices based solely on short-term rewards or stressors, we can easily get pulled off course. But when we connect our present decisions to something deeper, we’re more likely to stay grounded and resilient. In the Six Seconds emotional intelligence framework, this is called pursuing noble goals — the skill of aligning daily choices with a long-term vision that reflects your values. It helps us navigate complexity with clarity, even when the road ahead is uncertain.

The second layer of this lesson is emotional agility. Living a meaningful life isn’t just shaped by our circumstances — it’s shaped by how we respond to them. Building the emotional and cognitive skills to navigate the twists and turns of life makes it possible to keep growing, even when things fall apart. Over decades, it’s this capacity to adapt and move forward with purpose that defines the good life.

“To be able to study lives in such depth, over so many decades, it was like looking through the Mount Palomar telescope”

– George Vaillant on discovering the Grant Study

2. Emotional intelligence shapes our experience and outcomes

One of the most consistent findings in the Harvard Study of Adult Development is that how we respond to life’s inevitable challenges plays a defining role in the quality of our lives. Over decades, researchers — including Dr. George Vaillant, who led the study for over 30 years — found that certain emotional coping strategies, which he called “adaptations,” powerfully influenced not only psychological health but also physical wellbeing and longevity.

Vaillant categorized these strategies into three levels: immature, neurotic, and mature. While immature adaptations — like denial or projection — were linked with poor outcomes, mature adaptations enabled participants to grow through adversity and live more fulfilling lives. Crucially, many men in the study developed healthier emotional responses over time, suggesting that these skills are not fixed traits but learnable competencies.

These findings closely align with the skills in the Six Seconds Model of Emotional Intelligence:

- Altruism → Contributing to others’ wellbeing (Increasing Empathy)

- Anticipation → Imagining constructive outcomes (Exercising Optimism)

- Suppression → Choosing to delay action or impulse (Applying Consequential Thinking) and to an extent, recognizing patterns

- Sublimation → Channeling emotions into growth and creativity (Navigating Emotions & Pursuing Noble Goals)

- Humor → Maintaining perspective and resilience (Enhancing Self-Awareness)

As people aged, they became more likely to rely on these mature adaptations. Between ages 50 and 75, for instance, participants were four times more likely to use these emotionally intelligent strategies than immature ones. This supports a growing body of evidence showing that emotional intelligence increases with age, and more importantly, it can be strengthened at any stage of life.

The updated research in The Good Life (2023) by current study directors Dr. Robert Waldinger and Dr. Marc Schulz reaffirms that these emotional capabilities not only support mental health and resilience — they shape the very purpose of our lives. Emotional intelligence is the bridge between hardship and meaning, between stress and connection. It’s not just how we cope that matters, but how we grow through the experience and use it to deepen our purpose and relationships.

Overall, the Grant Study highlights 3 different aspects of emotional intelligence that have been backed up by other research:

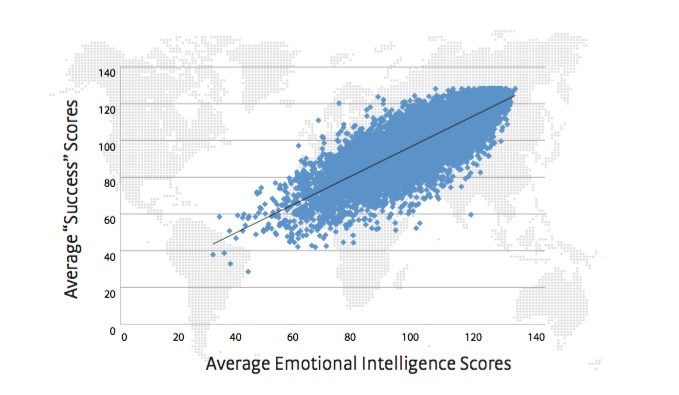

- Emotional Intelligence is highly correlated with personal and professional success.

- Emotional intelligence skills are learnable and measurable.

- Emotional Intelligence tends to increase with age, though the correlation is slight.

Ultimately, as Vaillant reflected after decades of analyzing the data, “The only thing that really matters in life is your relationships to other people.” Emotional intelligence is what allows us to build, maintain, and cherish those relationships — and live purposefully because of them.

3. Relationships are the most important factor in long-term happiness

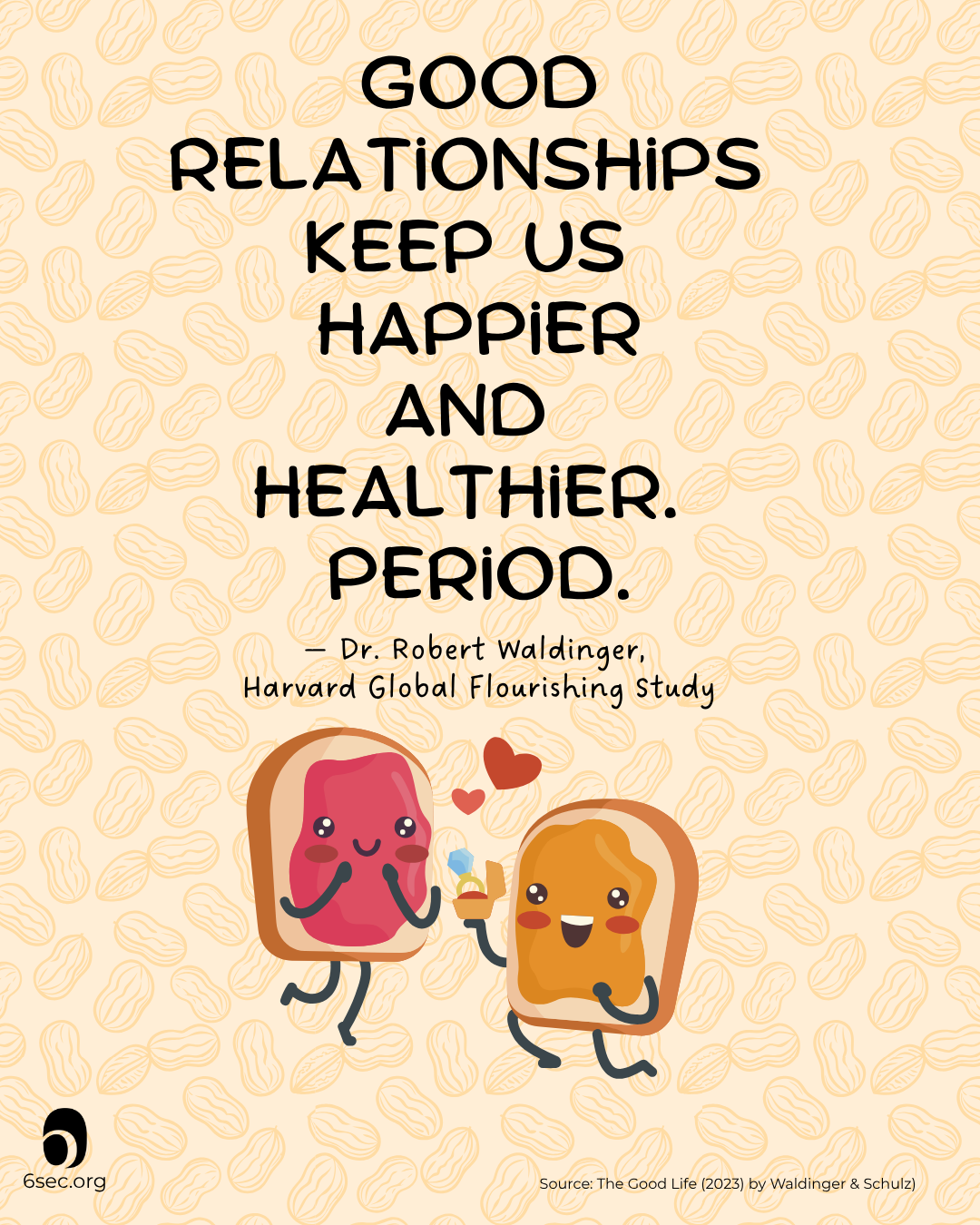

Across more than eight decades, the clearest and most consistent finding from the Harvard Study of Adult Development is this: the quality of our relationships—emotional warmth, trust, and support—is the single most important predictor of long-term happiness and health. It’s not how many people we know, but how safe and truly connected we feel.

Strong, positive relationships protect us from stress, strengthen our immune systems, and promote faster recovery from illness. By contrast, loneliness and social isolation pose health risks comparable to smoking or alcoholism. This deep connection between relationships and wellbeing extends beyond family or marriage, embracing friendships, community ties, and even small daily interactions.

As Dr. Robert Waldinger, current study director, says, “Loneliness kills. It’s as powerful as smoking or alcoholism.” The warmth and depth of a person’s bonds predict everything from emotional resilience to longevity and cognitive health.

“When the study began, nobody cared about empathy or attachment,” recalled Dr. George Vaillant. “But the key to healthy aging is relationships, relationships, relationships.” The data makes this strikingly clear: close relationships — not wealth, fame, social class, or even IQ — are what keep people happier and healthier throughout life.

The men’s relationships at age 47 predicted their well-being in later life more than any factor except their ability to adapt to life’s challenges. Relationships and adaptations are deeply interconnected: how we respond to hardship is shaped by the support around us, and our capacity to form and maintain bonds is part of how we adapt.

The study found strong links between flourishing lives and deep connections with family, friends, and community. Participants with the warmest connections were significantly less likely to develop heart disease, diabetes, or arthritis, and they experienced better immune function and faster recovery from illness. People who engaged more socially had a slower rate of cognitive decline in later life.

Even marriage had a measurable impact: married women lived 5–12 years longer on average, and married men 7–17 years longer, compared to their unmarried peers. These benefits held true when the quality of the relationship was positive, emphasizing that it’s not just being connected, but being meaningfully connected.

Those lacking strong connections faced higher risks of disease, depression, and early death.

And this goes far beyond marriage or family ties. The benefits of connection extend to friendships, workplace bonds, community involvement, and even small daily interactions. In The Good Life (2023), Waldinger and co-author Dr. Marc Schulz emphasize that small, consistent efforts to invest in relationships have a compounding effect on life satisfaction.

One of the most powerful insights is that relationships aren’t just about who we know — they’re about how we show up. According to Six Seconds’ emotional intelligence data, individuals with high EQ are 38 times more likely to have strong, high-quality relationships. That’s because emotional intelligence is inherently relational: empathy, self-awareness, and impulse control are the very skills that help us build and sustain closeness. People who have these abilities form strong bonds — and they reap the benefits.

As Waldinger shared:

“It’s easy to get isolated, to get caught up in work and not remember, ‘Oh, I haven’t seen these friends in a long time.’ So I try to pay more attention to my relationships than I used to. It’s useful to know — it’s a choice worth making.”

As Waldinger and Schulz emphasize, relationships are not a luxury—they are the foundation of a meaningful life. We don’t need to be extroverts or have hundreds of friends. We just need a few people we trust, and the courage to keep showing up for them—and for ourselves.

What Makes a Good Life? Insights from the longest study on happiness, The Harvard Grant Study

The Grant Study, also known as the Harvard Study of Adult Development, is one of the most comprehensive longitudinal studies ever done. Researchers set out to answer a seemingly simple question: what makes a good life? But as the decades passed, it became clear this question is remarkably complex. To find answers, they followed hundreds of men through college, marriage, war, parenthood, life crises, and old age — collecting a wide range of data about the men’s physical and mental wellbeing.

Dr. Arlie Bock, a Harvard physician, began the project in 1938 with his patron, department store magnate W.T. Grant. Starting with 268 Harvard sophomores between 1939 and 1944, including a young John F. Kennedy, Bock aimed to move beyond medicine’s usual focus on the sickly by studying successful, “normal” men to discover what constitutes a good life and perhaps a general recipe for success.

The participants agreed to a wide range of interviews, questionnaires, physicals, and extensive physiological measurements, forming the foundation of the data collected.

But unfortunately, like most longitudinal studies, enthusiasm waned after the initial burst of excitement. After about a decade, Grant withdrew funding, and by the mid-1950s the study was nearly abandoned.

A group of researchers led by Charles McArthur kept the thread alive by sending periodic questionnaires to the participants every couple years. Funding came from a variety of groups, ranging from the Rockefeller Foundation to the cigarette company Philip Morris.

Then two major developments changed the study’s fortunes. First, as the men reached middle age in the 1960s, many achieved dramatic success. Four ran for U.S. Senate, one became president, another a best-selling author. And then in 1967, a young psychiatrist named George Vaillant discovered the Harvard study, and fell in love with the possibilities it presented. In Vaillant, this amazing dataset had found its chief supporter and storyteller — and the project picked back up full force, now including a second cohort of 456 disadvantaged inner-city youths from Boston, known as “The Glueck Study,” adding much-needed diversity to the study.

The study’s participants experienced remarkable personal and professional successes, faced tragedies and heartbreaks, and encountered everything life offers in between. By examining the rich data alongside these varied life outcomes, patterns begin to emerge — offering us valuable insights into what contributes to a fulfilling and well-lived life. From these patterns, three key lessons stand out.

The Harvard Grant Study adds to the growing pile of evidence about the importance of emotional intelligence… These skills are strongly correlated with success, essential to navigating life’s ups and downs, and learnable.

The Harvard Grant Study Today: New Generations and Deeper Insights and Why Relationships Matter

What began in 1938 as a study of Harvard sophomores has expanded into one of the most remarkable ongoing research projects in the world.

Today, under the direction of psychiatrist and professor Dr. Robert Waldinger, the Harvard Study of Adult Development follows more than 1,300 children of the original participants. This expansion allows researchers to explore how the quality of childhood, relationships, and life experience ripple across generations.

The study has also broadened in other key ways: more diverse voices: by including spouses and partners over the past decade, the study brings in greater diversity across gender, background, and relationship experiences — offering a fuller picture of what helps people thrive. Modern tools for timeless questions: from genetic markers to brain imaging and stress hormone data, today’s research integrates biological data with psychological and relational insight. This means scientists can now see how early life experiences “get under the skin” and shape our lifelong emotional and physical health.

What hasn’t changed? The central finding that continues to echo through decades of data:

“The clearest message we get from this 85-year study is this: Good relationships keep us happier and healthier. Period.” – Dr. Robert Waldinger

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our free Practicing EQ eBook. These evidence-based exercises will not only enhance your ability to understand and work with your emotions, but will also give you the tools to foster the emotional intelligence of your clients, students or employees.

What the Latest Research Adds

Building on decades of data, the most recent synthesis from The Good Life (2023) by Drs. Robert Waldinger and Marc Schulz highlights important new insights:

- Loneliness is as harmful as smoking or obesity. Chronic disconnection impacts the body similarly to smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

- Quality matters more than quantity. It’s not how many people you know, but how safe, seen, and supported you feel that truly matters.

- Close relationships help regulate stress. Supportive bonds act as a buffer against life’s emotional and physical challenges.

- Relationships are living systems. Like our bodies, they need care, attention, and nourishment to grow and thrive.

- Emotional intelligence makes connection possible. Skills like empathy, vulnerability, and self-regulation allow us to build and sustain meaningful relationships over time.

Together, these findings reinforce the enduring truth of the study: connection isn’t just comforting — it’s essential for health, happiness, and longevity.

Director Robert Waldinger’s Top Takeaways: Building a Good Life

So, what does all this mean for us?

That the foundation of a good life isn’t a big secret. It’s something we can start cultivating today. It’s in the small moments: checking in with a friend, holding space for a child’s emotions, taking a breath before reacting, reaching for kindness when it’s hardest.

As Waldinger puts it, “Relationships are messy and they’re complicated. But the good life is built with good relationships.”

If we want to live well, we must learn to love well. And that means developing the emotional insight, empathy, and courage to keep showing up — for ourselves and each other.

What about you? Do these findings confirm or challenge your beliefs about what makes a good life? We’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

🛠 Build Your Good Life: 5 Ways to Start This Week

Inspired by The Good Life (2023) by Waldinger & Schulz

- Text or call one close friend just to check in.

- Plan a connection ritual—weekly walks, dinner, or coffee.

- Practice micro-connections: eye contact, smiling, greeting neighbors.

- Reflect on your ‘support map’: Who do you trust? Who trusts you?

- Repair a rift—take a small step toward mending a strained relationship.

Small moments of connection, repeated over time, are what build a meaningful life.

If emotional intelligence helps us connect, how do we actually practice it in daily life?

Our Practicing EQ ebook offers simple, research-backed exercises to grow emotional intelligence—like mapping your support network or tuning in to your feelings before a tough conversation. Whether you’re strengthening existing bonds or opening space for new ones, the key is presence, intention, and care.

FAQs

What is the Harvard Grant Study?

The Harvard Grant Study is one of the longest-running and most comprehensive studies on adult development and wellbeing. It began in 1938 by tracking a group of Harvard sophomores to understand what leads to a happy, healthy life. Over the decades, it gathered detailed data on participants’ physical health, mental wellbeing, relationships, and life experiences, providing deep insights into the factors that contribute to a good life.

What is the key finding from the study?

The most consistent discovery is that good relationships keep us happier and healthier throughout life. This applies broadly across emotional wellbeing, physical health, longevity, and cognitive resilience. Close, warm, and stable relationships are a stronger predictor of life satisfaction and health than wealth, IQ, or fame.

Has the study changed over time?

Yes, the study expanded beyond the original group of Harvard sophomores to include disadvantaged youths and, more recently, the children, spouses, and partners of the original participants. This broadening has increased diversity in gender, background, and life experiences, providing a fuller picture of what helps people thrive.The research now focuses more deeply on the emotional warmth and quality of relationships, not just their existence.

Is the Harvard Study’s finding supported by broader science?

Yes. Research shows that loneliness and poor social connections dramatically increase health risks, comparable to smoking 15 cigarettes a day or obesity. The World Health Organization has recognized loneliness as a serious public health concern due to its widespread impact on mental and physical health. This supports the Harvard Study’s emphasis on the vital importance of close, supportive relationships.

Explore more

Learn practical tools for emotional intelligence and get the latest trends on EQ in our free resources at: