Name It to Tame It: How Naming Your Emotions (“Affect Labeling”) Lowers Stress and Builds Emotional Intelligence

by Michael Miller and Alexandra Tanon Olsson

When you’re anxious, angry or upset, do you wish you had a magic button to calm yourself down? Well, I have good news. Recent neuroscience reveals a remarkable attribute of our brains that isn’t exactly a magic calming button, but it’s pretty darn close.

by Michael Miller

Why Naming Emotions Works: The Neuroscience of Affect Labeling

It’s a little after 3 pm, and I am stopped cold in traffic. I look ahead and see red brake lights for miles. “Ugh, Highway 1,” I mumble to myself.

I was running late and feeling frustrated. I even caught myself thinking negative thoughts about other drivers who had to switch lanes in front of me, which is never a good sign about my emotional state.

Then I thought to myself, “It’s not his fault. You are frustrated because you are stuck in traffic.”

And oddly, I felt a lot better. I relaxed my shoulders, turned on the radio, and continued to sit in traffic – but with less tension. It seemed like the simple act of recognizing my frustration to myself really helped. This seemed absurd, because if you had asked, I would have told you that I knew exactly what I was feeling – frustrated! – and recognizing it would only make it worse. But in reality, I felt a lot better. As it turns out, there is a scientific basis to this phenomenon.

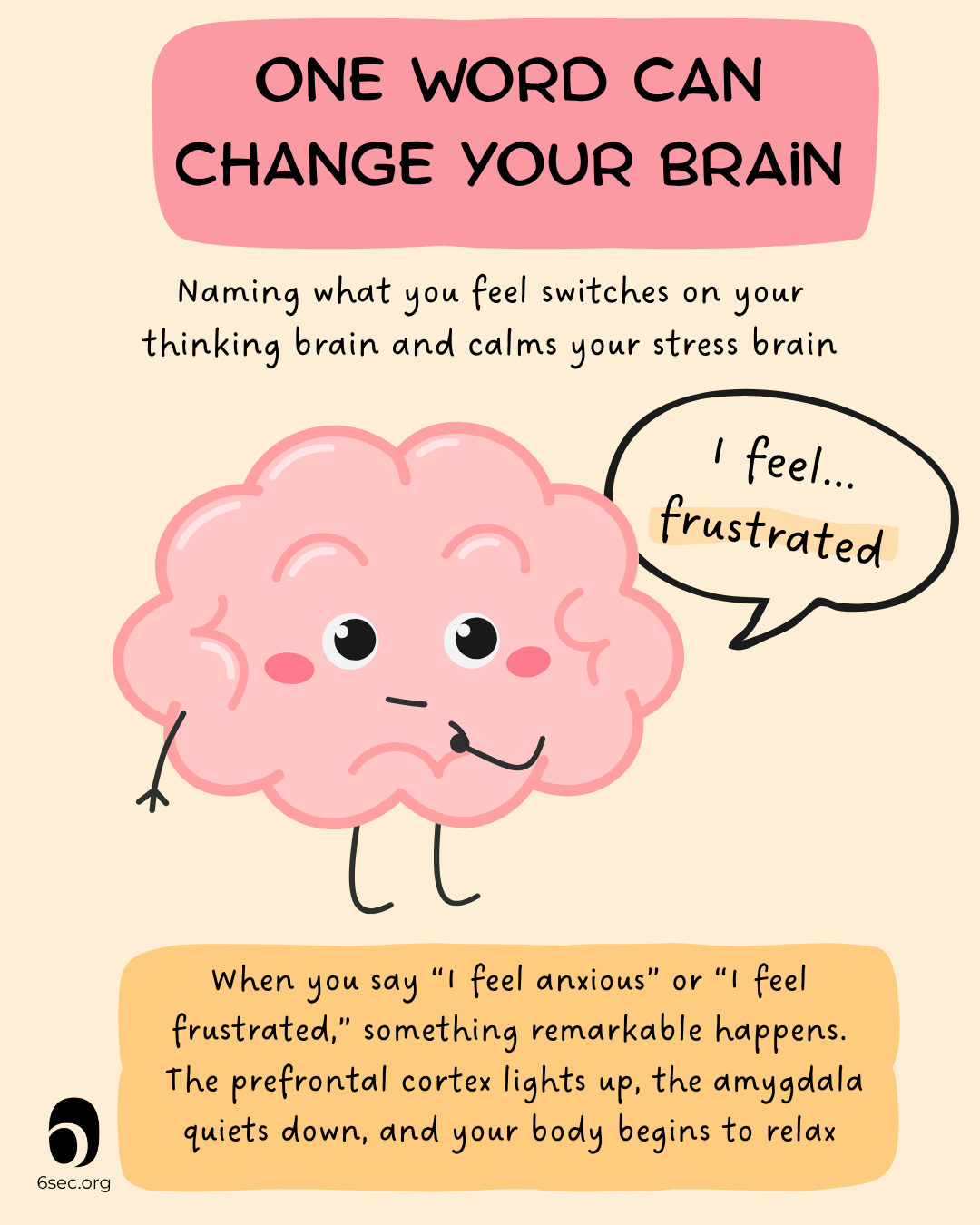

In fact, scientists have shown that naming our emotions, also known as affect labeling, isn’t just a feel-good trick. It actually changes what’s happening in the brain. When you put feelings into words, the prefrontal cortex — the part of your brain that helps you plan, focus, and make decisions — switches on, while the amygdala — the alarm center that fuels stress — quiets down.

What is affect labeling? Affect labeling—“naming your feelings”—is the practice of putting an emotion into words (e.g., “I feel anxious”). Doing so engages brain regions for control and perspective, which reduces stress reactivity and makes it easier to choose a helpful response.

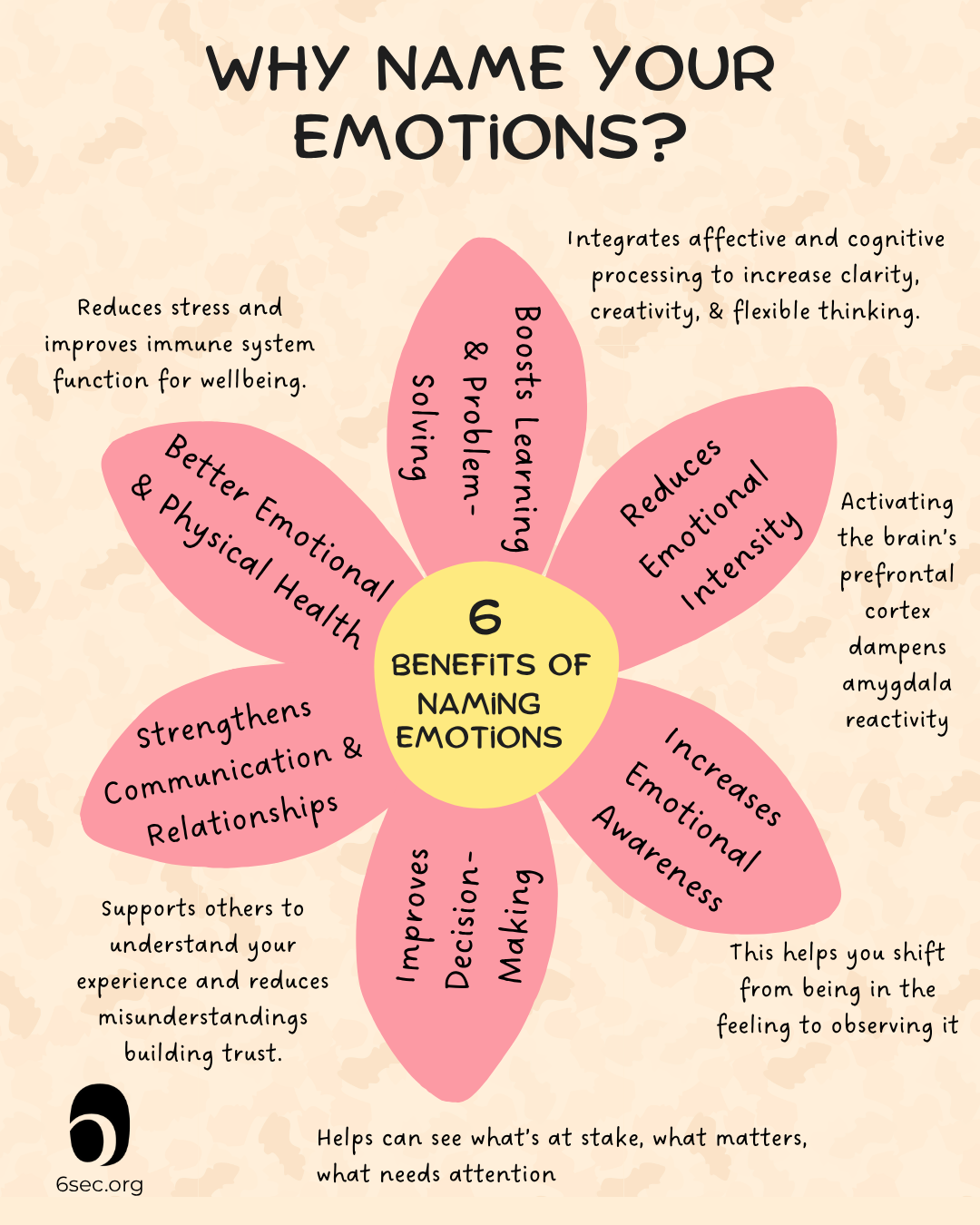

When the prefrontal cortex comes online, something remarkable happens. Your working memory strengthens, which means you can hold on to perspective instead of reacting impulsively. You also gain the ability to reappraise what’s happening — to reinterpret that racing heart or sweaty palms as excitement rather than anxiety. Over time, each time you practice naming emotions, you’re literally training your brain. New neural pathways form, making it easier to calm down, recover quickly, and respond with resilience the next time strong feelings show up.

But the impact doesn’t stop in your head. When your brain shifts out of “alarm mode,” your whole body responds. Your heart rate slows, your muscles release tension, and stress hormones like cortisol begin to drop. That physical calm then gives your mind space to process information more clearly. Instead of reacting automatically, you can pause, reflect, and choose a response that actually serves you.

Over time, this practice reshapes your life in practical ways. You make better decisions because you aren’t hijacked by fear or frustration. You strengthen relationships because you can name what you’re feeling instead of lashing out. And you show up more authentically, because your emotions become data to guide you — not forces that control you.

Feelings are temporary and they give us the opportunity to pause, listen, and choose how we want to respond.

The Proven Benefits of Naming Emotions for Stress, Confidence, and Performance

Consider this experiment from the University of California at Los Angeles. Dr. Michelle Craske tested out this hypothesis about labeling emotions with a group of participants with a fear of spiders. She started the experiment by having them approach a large, live tarantula in an open container outdoors (you read that correctly) – and told them to keep getting closer until they touched it, if they could get far. Then the participants were brought inside, put in front of another live tarantula in a container, and divided into four groups, based on the instructions they were given for how to think about the spider.

The first group was asked to describe the experience of being around the spider and label what they were feeling. For example, “I’m scared of that huge, hairy tarantula.” Now this is actually a radical way to respond. Normally the goal is to make people think differently about the spider so that it appears less threatening – and this is exactly what the second group was instructed to do. They would say, for example, “The spider is in a cage and can’t hurt me, so I don’t need to be afraid.” The third group was instructed to say something that was irrelevant to the spider, and the fourth group was simply exposed, not instructed to say anything at all.

One week later, all the participants were re-exposed to the live tarantula in the outdoor setting, and told to get as close as possible, and touch it with a finger if they could. Dr. Craske and her colleagues measured how close all the participants got to the spider, how distressed they were, and their physiological responses, specifically how much the participants’ hands sweated, which is a good measure of fear. So what did they find? The group that labeled their fear of the spider performed far better than the other groups. They got closer, were less emotionally aroused, and their hands were sweating significantly less. Like with my own labeling of my frustration in traffic, the recognizing and naming of emotions seemed to defang the fearful emotions.

Labeling emotions reduces fear responses: “The group that labeled their fear of the spider performed far better than the other groups: they got closer, were less emotionally aroused, and their hands were sweating significantly less.”

The same principle applies in everyday life. Whether it’s social anxiety, public speaking nerves, or a tense meeting at work, people who take a moment to name what they’re feeling perform better and recover faster. This matters because when we give our emotions a name, and especially when we give them a more helpful name, cortisol levels come down more quickly, and confidence rises because our brain perceives the situation as a challenge we can meet, not a danger to escape. Over time, this ability to re-label emotions builds resilience: we bounce back sooner, think more clearly under pressure, and carry ourselves with greater confidence.

Why does simply saying “I’m anxious” or “I’m excited” make such a difference? Research shows that naming your feelings acts as a bridge between raw experience and conscious awareness. Instead of being swept away by the emotion, you’re grounding it in language — which engages the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s center for reasoning and self-control. That shift creates a sense of perspective: you’re not all anxiety, you’re a person experiencing anxiety.

Brooks’ study also found that reframing “I’m anxious” into “I’m excited” was especially powerful because both emotions are high-energy states. The body is already revved up — heart racing, breath quickening, adrenaline flowing. Trying to “calm down” fights against that energy. But shifting the label to “excitement” takes the same physical arousal and gives it a positive meaning. Suddenly your body’s stress response becomes fuel for performance instead of a threat to manage.

We are not defined by our emotions. Feelings are temporary and they give us the opportunity to pause, listen, and choose how we want to respond. When we remember that we are greater than what we are feeling in that moment, we can be at peace with the feeling, and simply listen to what that emotional data is trying to tell us. So next time you are feeling a difficult emotion, start by labeling it: I am angry, or sad, or anxious. Just tell it like it is.

When we give our emotions a name… cortisol levels come down more quickly, and confidence rises because our brain perceives the situation as a challenge we can meet, not a danger to escape.

How to Start Naming Emotions: Simple, Science-Based Practices

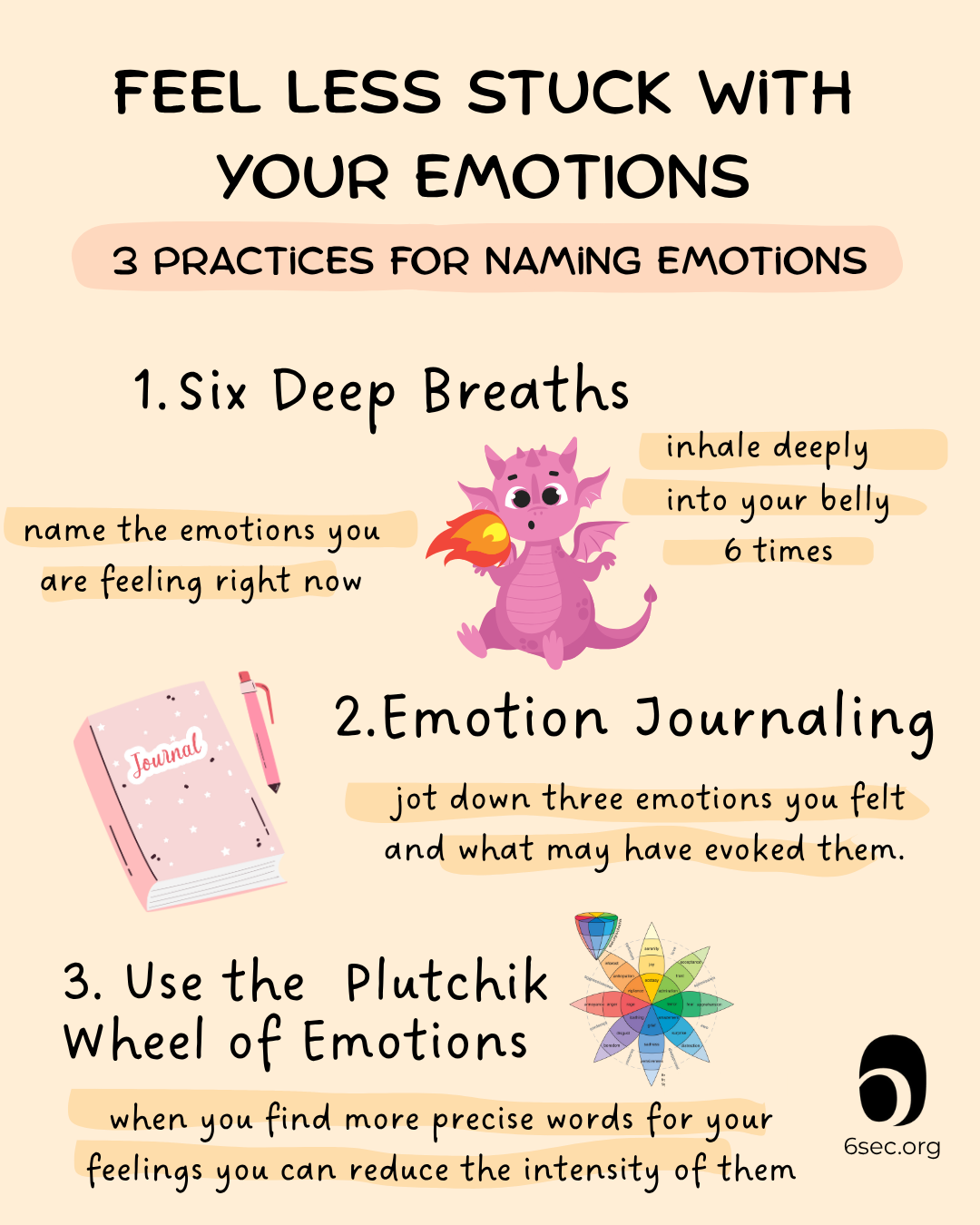

- The 6-Second Pause: When strong emotions hit, your brain floods with neurochemicals that drive reactivity. Those chemicals begin to settle in about six seconds. By pausing in that space, you give your cortex (thinking brain) time to step in and quiet the amygdala (reactive brain). This simple pause creates a moment of choice—so instead of reacting automatically, you can respond intentionally.

- Emotion Journaling: At the end of the day, jot down three emotions you felt and what triggered them. Over time, you’ll start noticing patterns.

- Use the Wheel of Emotions: If “frustrated” or “stressed” feels too broad, tools like Plutchik’s Wheel help you find more precise words. Sometimes what feels like anger is actually disappointment—or worry.

The 6-Second Pause creates a moment of choice—so instead of reacting automatically, you can respond intentionally.

The Six Seconds Model: Know → Choose → Give

Making our emotions less intense is great, but that isn’t really the end goal. It simply cracks open the door, and calms down our emotional response so we can combine our thinking and feeling more effectively – and that is what practicing EQ is all about.

In fact, this is exactly the process described in the Six Seconds Model: a practical framework for moving from raw reaction to intentional action.

Here’s how the process unfolds step by step:

- Step 1: Know Yourself — What am I feeling?

The first step is to pause and name your emotions. Simply identifying what you’re feeling helps calm the body and nervous system. With that awareness, you begin to see more clearly instead of being swept along by stress. - Step 2: Choose Yourself — What choices do I have?Once emotions are named, stress levels decrease and reasoning, creativity, and problem-solving return. In this calmer state, you can pause, consider your options, and make intentional decisions about how to respond.

- Step 3: Give Yourself — What do I truly want?Finally, emotional intelligence calls us to act with purpose. By asking what you really want in the bigger picture, you can align your actions with deeper values and priorities—so your response reflects not just the moment, but what matters most to you.

- When we name emotions, we aren’t just soothing ourselves — we’re creating the conditions to think clearly, make choices aligned with our values, and ultimately show up with purpose.

- Take fear or stress for instance. When we are afraid or stressed, our brain can only respond based off of previously stored patterns of behavior. Evolutionary, this makes sense. Evaluating your options when you see a tiger guarantees that the only outcome is the tiger eating you. So when our brain perceives a threat, it only lets you respond off of previously stored patterns, which you can enact instantaneously. But that is rarely the best possible reaction, unless you really are reacting in a life or death situation.

- The lowered intensity of our emotions after we name them allows us to take it a step further, and ask:

- What choices do I have? — this reflects the Choose Yourself step of the Six Seconds Model of Emotional Intelligence, known as KCG: Know, Choose, Give. Here, we pause and recognize that we have options.

Then we can ask:

- What do I really want? — this is the Give Yourself step, where we align our actions with our deeper values and purpose.

But just naming your emotions is a great way to start practicing EQ. Try it out next time you feel stuck, and share your story below!

Every time you name an emotion, you are strengthening your brain’s capacity for balance and resilience. That is how we begin to get unstuck, one word at a time.

Resources to Deepen Emotional Awareness

Sometimes we don’t know exactly what we’re feeling, or we don’t have the words to describe it, which makes naming our emotions difficult. That’s why emotional literacy is the foundation of practicing emotional intelligence. Emotional literacy is the ability to recognize, label, and understand emotions in yourself and others; it’s the foundation of emotional intelligence and a skill that can be learned.

If you want practical tools, start with the Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions to expand your emotional vocabulary, and grab the free Practicing EQ eBook for exercises you can use immediately.

Naming emotions is simple, but powerful. It calms the body, clears the mind, and opens the door to wiser choices. Neuroscience confirms that this small habit shifts your brain from a reactive state into a more thoughtful one, which improves your decisions, your relationships, and even your long-term well-being.

So today—pause for a moment. Take a breath. Notice what you’re feeling, and put it into words. It may seem small, but every time you name an emotion, you are strengthening your brain’s capacity for balance and resilience. That is how we begin to get unstuck, one word at a time.

FAQ About Naming Emotions (Affect Labeling)

- Does naming emotions make them stronger?

Usually the opposite: labeling creates distance and reduces reactivity, which helps you regulate. - Is naming emotions the same as venting?

No. Venting rehashes the story; labeling simply identifies the emotion so you can choose a constructive response. - What if I can’t find the exact word?

Start broad (“tense”), then refine using a tool like Plutchik’s Wheel: tense → worried → apprehensive. Precision builds with practice. - Can this backfire at work?

Not if you keep it simple. Use brief, neutral labels — for example, “I’m frustrated; I need a minute to regroup” — and follow with a constructive ask. - Will naming my emotions make me dwell on them more?

Surprisingly, no. Neuroscience shows that putting feelings into words actually reduces their intensity by calming the brain’s alarm system. Rather than amplifying the feeling, labeling helps you process it and move on more quickly. - What if I don’t know exactly what I’m feeling?

That’s normal. Start with a broad label like “stressed” or “upset.” Then use tools like Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions to find more precise words. Even something as simple as “I feel off” begins to create space for clarity.