Based on fascinating neuroscience and psychology research, here are 7 decision making insights that will help you make better decisions:

1. Generating at least 3 options is a game changer. According to research from Ohio State University, we make better decisions when we generate at least 3 options to consider. Dr. Therese Houston, a decision making expert and author of How Women Decide, sums up the problem this way: ““All too often we only give ourselves one option and we fool ourselves into thinking it’s actually two. Should I do this or not? There’s really only one option on the table – I’m going to make this change or I’m going to stay put. And if you give yourself three options, it gets you thinking outside the box.”

She went on to use this business example: “Your company’s thinking about building a parking garage. So instead of just, should we build a parking garage or not, three options would be, should we build a parking garage, should we give all employees bus passes, or should we give our employees the option to work from home one day a week?” It’s the emotional intelligence skill of exercising optimism at work here – the ability to generate new options and invent solutions to “unsolvable” problems.

If you want to be sure you’re making the best possible decisions, practice generating at least 3 options. If you’re like me, that means getting out some Post It notes.

2. Leaving emotions out of it is actually a disaster. To make good decisions, you simply need to “be rational” and “keep emotions out of it,” right? That’s what most of us, myself included, have learned. And for many decades, that’s been the thinking in the scientific community, too: cognition and emotion are two separate systems in the brain, and we need to keep our emotions from interfering with our higher level cognitive processes. The only problem is that this has turned out to be completely wrong. Of all these decision making insights, this is probably where the biggest gap is between what most of us have been taught to think and what research has found to be true: Leaving emotions out of it isn’t good for decision making; it’s a disaster. In a fascinating study of patients with brain damage to a specific part of the frontal lobe, researchers found that rational thought is of little practical use without emotions. These patients had not lost their logical reasoning abilities – they knew what made a good business investment, the social norms that should guide one’s behavior, etc. – but without past emotional knowledge to guide the reasoning process (which they lost due to the brain damage they suffered), they continually made disadvantageous decisions. Emotions are not in the way of cognition, but serve as a stabilizing and motivating force to put logical thought into action.

Leaving emotions out of it leads to bad decisions. A much better, smarter way to treat your emotions is like data. And when you’re making a decision, you want all the relevant data you can get.

3. Checking your emotional state is essential. While leaving emotions out of it is bad for decision making, emotions are not innocent bystanders: a growing body of research shows that different emotions impact our decision making in really profound ways. So to be an expert decision maker, you need to able to recognize and name what you’re feeling, and understand how that could influence your decisions, often subconsciously.

Anger, for example tends to instill confidence and make people more eager to act. When people are experiencing anger, they are more likely to take risks and minimize the potential damage of those risks. I know I have definitely made rash decisions when angry – and later regretted them. Overconfidence can be fatal to good decisions.

Sadness, on the other hand, tends to foster systematic thought: “on the one hand x, but on the other hand y.” When people are experiencing sadness, they are more likely to evaluate and compare all the options. At its extreme, this can be paralyzing.

Fear tends to limit the options that we see, because of the amygdala activation discussed in detail below. When its activated, our brains can only choose options based on our previously stored patterns.

Happiness even makes us biased. Research has found that happiness tends to make people more gullible. According to a number of studies, people who are experiencing prolonged happiness are more likely to put faith in the length of a message, or in the attractiveness or likability of the source, rather than its quality.

There is not a good or bad mood to make decisions in – though fear, as discussed, can be quite limiting – the key is to be aware of how you’re feeling and how that could impact your decision making. And another trick, once you label how you’re feeling, is to say it loud and proud…

4. Naming emotions calms the amygdala and opens up possibilities. When we name our emotions, and say, “I am frustrated,” or “I am angry,” it actually lessens the intensity of that feeling, and opens the door for us blend thinking and feeling in a more optimal way. Physiologically, here’s what happens… When we’re feeling a strong emotion, our amygdala is activated, which is the “fight, flight or freeze” response center. But it’s a part of the brain that’s designed to make quick, life saving decisions – so we can only choose options based on our previously stored patterns. That’s fine when you’re truly running from a tiger: you don’t need that many options, and speed is of the essence. But when we’re dealing with a more complex stress-inducer, it’s a catastrophe for decision making. Labeling how you’re feeling calms the amygdala and activates the cortex, the thinking part of the brain, so you can generate those options that are essential to decision making.

So say it like it is, “I feel angry or sad or frustrated.” It calms the amygdala and opens up the door for us to use our emotional intelligence and make the best possible decisions. For more on the power of naming emotions, check out Getting Unstuck: the Power of Naming Emotions.

5. Pausing even a fraction of a second gives you time to focus on what’s important. Dr. Jack Grinband’s research at the University of California Davis has found that “postponing the onset of the decision process by as little as 50 to 100 milliseconds enables the brain to focus attention on the most relevant information and block out irrelevant distractors.” When you consider the fact that we filter out more than 99% of the stimulus that hits our eyes, ears, and noses every day, it makes sense that sometimes we make bad decisions due to not focusing on the most relevant information. And even though the slightest of pauses can help, we recommend pausing for six seconds – the amount of time it takes emotion chemicals to be fully absorbed after release. And how our emotional intelligence non-profit got its name.

Pausing for six seconds not only gives time to focus on what’s immediately relevant, but you can step back and think about the bigger picture, too. In the Six Seconds Model of Emotional Intelligence, this is the skill of pursuing noble goals – connecting your every day choices with your bigger purpose. And when you pause to do that, you are going to make more authentic, powerful decisions based on your long-term goals. It’s powerful stuff.

6. Recognizing your unconscious bias wards off attribution errors. The most common example of this is hunger and the tendency to think of things as worse or more negative when we’re hungry than we normally would. Hence the new English word hangry – basically to be angry or frustrated because of hunger. But unless we’re consciously aware that we’re hungry and how this could be impacting us, we simply go about interpreting the world and making decisions in a biased way, without knowing it. And this is more common than you’d like to think. Consider these sort of alarming examples from the research world.

A study in Israel found a correlation between committees’ decisions to grant parole (or not) and how recently the members had eaten lunch. That’s right. The decision on people’s freedom was strongly influenced by hunger and they didn’t know it. A study of college admission officers in the United States similarly found that the time of day when the officers graded essays played a big role in determining how they graded them. And finally, a study from the University of Toronto in Canada found that external factors can skew our perceptions. They found that the brightness of a room tended to amplify people’s emotions and impact the decisions they made about the spiciness of food and attractiveness of people. All these studies point to the same finding: unconscious bias is real, and the only solution is to shine the bright light of awareness on it. We should ask ourselves more, “What are some aspects of my external or internal state right now that could impact my decision making?”

And if you’re unsure, hold off until after lunch or until you’re in a space with calmer lighting, and then make a decision.

7. Removing yourself completely actually leads to wiser, better decisions. Have you ever heard of Solomon’s Paradox? It’s the theory, proven true by recent research, that people tend to reason more wisely about other people’s problems then their own.

In the experiments at the University of Waterloo, one group of participants imagined that they had been cheated on by their partner, and the other group imagined that their friend had been cheated on by their partner. Then both groups filled out a questionnaire aimed at measuring wise reasoning about the situation – the ability to take others’ perspectives, recognize the limits of one’s knowledge, and see many possible solutions. And what did they find? The group that imagined their friend being cheated on scored higher on all these measures of wise reasoning, seemingly more able to reason wisely and make good decisions about the situation than those who pictured themselves in that same situation. But then the researchers switched up the experiment and found something unexpected – and promising.

In the revised experiment, the group that imaged themselves being cheated on split up into two groups. The first imagined being cheated on from a typical first-person perspective, asked themselves questions like, “Why am I feeling this way? What are my thoughts and feelings about this?” But the other group thought about being cheated on from a third-person perspective – like they were looking in on themselves and their relationship. They asked questions about themselves in the third person, like, “Why does he or she feel this way?” And this self-distancing strategy worked remarkably well. Those who thought about the situation from a 3rd person perspective scored just as high on the wise reasoning test as those who thought about their friend being cheated on.

So one trick to making better decisions is to pretend like you’re making a decision for a friend or observing your life. Just take yourself out of it completely! And then if it goes poorly, it’s not even your fault 🙂 I am kidding about not being at fault, of course, but research suggests that self-distancing is an effective stragety for making good decisions.

Thanks for reading and click on the button below to get your free poster, 7 Decision Making Insights Everyone Should Know.

What’s new in emotional intelligence?

Voices from the Network: Huong Nguyen

This month we sit down with Ms. Huong Nguyen, a medical doctor and certified EQ Coach, EQ Facilitator, Practitioner and Assessor who has been working to expand her local EQ community in Vietnam.

Voices form the Network: Jacqui Butler & Svetlana Suvorova

When Jacqui Butler and Svetlana Suvorova met in Six Seconds’ EQ Coach Certification program in 2022, they clicked right away. After building a strong connection of mutual support and collaboration, they recently launched a joint venture, LeadEQ, to support women leaders. This is their story of finding EQ, each other, and a deeply meaningful path of professional growth.

Voices from the Network : Pamela Chng & Suyin Tay

Today we talk to Pamela Chng and Suyin Tay, two social entrepreneurs based in Singapore who run Bettr Coffee, and its nonprofit affiliate, Bettr Lives, a Six Seconds Preferred Partner.

The Neuroscience of Change: How to Make New Year’s Resolutions Stick

Why do New Year’s resolutions nearly always fail? And what can we do to make them stick? Explore the neuroscience of change and motivation.

Voices from the Network: Liliana Rodríguez

This month we’re sharing the story of Liliana Rodríguez, an emotional intelligence consultant and coach based in Monterrey, Mexico.

Emotional Insights for Leaders: Apathy and How to Move Through It

In this Emotional Insights for Leaders, we look at an emotion that typically blocks progress but can also spark progress: Apathy.

- Pursue Noble Goals in the Six Seconds Model of EQ - July 29, 2023

- Increase Empathy in the Six Seconds Model of EQ - July 26, 2023

- Exercise Optimism - July 24, 2023

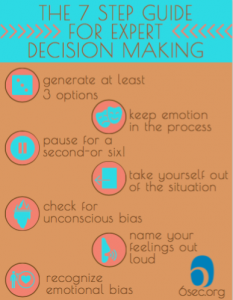

7 Step Guide for Expert Decision Making

7 Step Guide for Expert Decision Making

I use the Think Feel Act cards. First time on the site and I have to say I am very surprised to read in point 3, the labeling of “Happy People”, “Sad People” and “Angry People” used in this article. It seems counter to the intent of this entire organization. This use of labeling and generalization distracted me from the rest of the article. I would much more appreciate something along the lines of, “When people are experiencing anger while making decisions…” or “People in a high or prolonged state of happiness tend to…”

We have the capacity to be all these things and I would not enjoy the minimizing label of Angry Person, for example. Much like calling a kid a Bully versus a kid who is demonstrating bullying behaviors. We are much more likely to see the possibility of the kid.

Thank you Jules – I prefer the way you’ve framed this. I agree that it’s all-too-easy to label people instead of describing them.

Hi Jules, thank you for sharing. I think that is a valid critique and I prefer your framing, too. I did not intend to be labeling or generalizing, but I can see now that it comes off that way. By “angry people,” I simply meant “someone who is experiencing anger,” but that is an important distinction, and as you said, a crucial one that we are working to promote in our work. I have changed the text to reflect this better, less label-y framing!

Enjoyed the article. I can’t seem to download the checklist.

Hi Mark, there seems to have been a glitch preventing the download from working. I fixed it, so it’s working now! Let me know if it’s still not working for you, and I will make sure you get it! 🙂

Great article. You are providing not only information but also practical information on how to use these 7 Decision Making Insights along with the Guide. Thank you very much for your help.

Thank you, Stephanos! I enjoyed writing it. As we are a network of people supporting each other to practice emotional intelligence, the practical tips we share with each other are vital. Thank you for being a part of it!

I am a 67 yr. old semi retired psychiatric RN with 45 years experience.

I’m checking out your posting to see if I want to proceed as a member. So far :sound and wise.

Thank you Karen! And for your service as an RN.

Hi Karen, we’re thrilled to have you as part of the community!

im relay appreciate this article and I’m in accord of the general contest in more is first time say about the amygdala

Hi Serge! I’m glad you enjoyed the article!

What I like about the 6 seconds community is that it combines the intuitive nature of emotions with their scientific underlyings and actionable behaviors. What sticks to my mind the most is the fact that attempting to think of 3 options enables us to be more creative and optimistic. At the same time, distancing ourselves and looking at our problems from a third-person point of view helps us think clearer about the situations. A very action-provoking article!

Thank you, Nam! That is also what I love about this community. It’s about taking the theory of emotional intelligence and putting it into action. To form a community of people who are actively practicing and sharing these tips and strategies, and all together, making the world a better place. I am glad you enjoyed the article!