A multi-year intervention in an American chemical manufacturing plant led to a 91% improvement in employee engagement which was correlated with a 167% increase in production quality and an 83% decrease in reportable safety incidents.

The project focused moving away from a “safety program” and replacing that with a “culture of safety” based on a clear understanding of the organizational climate and new management practices focused on Relationship-Centered Leadership. The case is summarized in a key concept: Leaders Don’t Motivate – They Create the Conditions for Self-Motivation.

Do you have a safety culture, or do you have safety programs?

On the surface this question may appear easy to answer, but the distinction between programs and culture is deceiving. While many organizations believe that programs equate to culture, this inaccuracy can lead to serious consequences.

It’s like thinking the tip of an iceberg is the iceberg. We know from the story of the Titanic that this distinction can be the difference between thriving and tragedy.

Background: Engagement

Safety programs are analogous to the tip of the iceberg, and organizational culture is what lies below the water line—the heart of the iceberg. A positive safety culture can only exist within an organizational culture in which employees are positively engaged with their business, manager or supervisor, and daily work.

In late 2007 a speciality chemical manufacturing plant with 285 employees, based in the eastern United States, confronted reality: Their employees were disengaged, their safety record was not satisfactory, and the “safety programs” were not working. They needed a different approach.

Employee Engagement

It is not uncommon for safety consultants to focus their efforts on assisting organizations in developing and installing safety programs, but few consultants ask the key question, “How engaged is your workforce?” Although a focus on safety can have a positive impact upon an organization’s overall culture, it is not enough. If there remains a high percentage of disengaged employees, any programs put in place will fail to reach their full potential.

The Conference Board, a global, independent business membership and research organization working in the public interest since 1916, developed a definition for engagement that blends the key elements into one concise statement: “[A] heightened emotional and intellectual connection that an employee has for his/her job, organization, manager or coworkers that, in turn, influences him/her to apply additional discretionary effort to his/her work.”

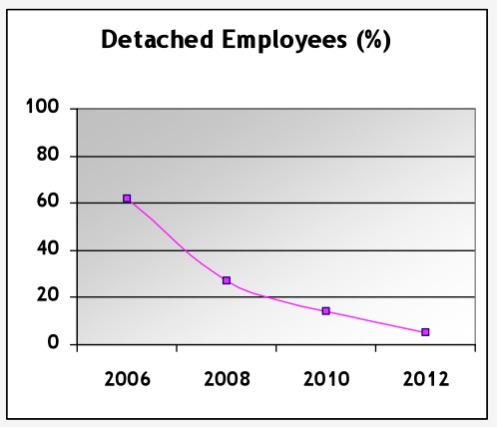

Imagine you are the manager of a chemical manufacturing plant and have finally received the results of your organization’s employee engagement survey. Holding your breath, you look for “the number”— the score that speaks volumes about your employees’ ability to work together and tackle the issues affecting safety and productivity. You hope your intuition is wrong, but then your eyes and the number meet: more than 60% of your workforce is detached or disengaged.

The plant’s leaders understood that if they wanted to transform their company’s culture, they needed to move from the tip of the iceberg to below the water line and into the heart of the iceberg. They needed to determine what factors were perpetuating the current culture of disengagement so they could transition to increased engagement and performance.

To prepare for change, the management team embarked on a number of data-gathering initiatives, including:

1. Administered the Six Seconds’ Organizational Vital Signs (OVS) climate assessment

2. Interviews with key external stakeholders

3. Individual employee interviews

4. Employee focus groups

5. Review of financial and production performance results, HR reports, and metrics from previous engagement surveys and safety performance data.

Findings from the OVS culture assessment process confirmed that the low morale was, indeed, negatively affecting the plant’s ability to perform as efficiently as employees, stakeholders, and managers believed was achievable. One employee, echoing the feelings of many of his coworkers and managers, stated, “We have tremendous possibilities and potential, but we can’t seem to find a way to make it all come together.’’Another added,

“We need to stop playing games and throwing safety program after safety program up against the wall hoping they will stick.”

The climate and culture factors that the OVS* assessed were:

Alignment: To what extent are people involved in their organization’s stated mission and its execution? Do they feel a sense of belonging within the organization?

Accountability: Do people in the organization see themselves and others following through on commitments? Are they motivated, and do they take responsibility for their choices and the outcomes?

Adaptability: Are people seeking change? Are they ready to adapt? Are they flexible problem-solvers, open to innovation?

Collaboration: How well do people interact with one another and share information? Do they solve problems together?

Leadership: What level of commitment do employees have to their leaders? How do they perceive their leaders and leadership throughout the organization? Are people capable, competent, and worth following?

Trust: Do people have a sense of faith and belief in the organization and its leaders? Can people rely on the integrity of their coworkers? Do they have confidence in others’ abilities and intentions?

The results were compelling. Management and staff were not on the same path, and their quality, safety, and productivity problems were the result of this divide. To initiate the next phase of change, the plant manager addressed his team.

“We cannot go on this way. If we are to achieve sustainable success, we must transform our culture. We’ve tried all the Band-Aids; applying one more is not the answer.”

Intervention: Leaders Walking the Talk

The plant leaders were thoroughly debriefed on the findings of the OVS results and came to the consensus that the plant’s ability to thrive was dependent upon building a culture or engagement.

They decided to concentrate their efforts on the following factors:

Alignment

Collaboration

Accountability

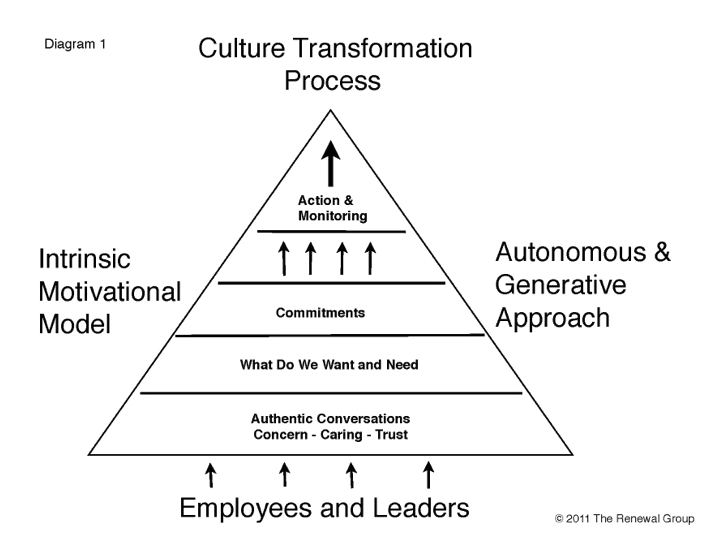

A three step process was initiated to address these factors. These steps were structured on a Culture Transformation Process shown in the diagram to the right.

Step One: Why

Diagnosing, comprehending, and developing a plan to transition from one culture to another culture is not a process to be taken lightly — it is a journey, and all journeys encounter challenges (or icebergs). Therefore, leaders must make an informed commitment to the process. Meaning they must have a compelling why that resonates with the organization. Without a compelling purpose and a realistic understanding of the work and commitment required, the resolve and persistence required by employees to stay the course will dissolve.

The leadership team undertook a new plant initiative: To work toward alignment with employees and their values in determining the compelling why that would propel the company forward. The result was the creation of the following Vision Statement:

Our vision is to create and sustain a great place to work where …

All employees can work safely and have pride in their jobs.

Employees are treated with respect.

Employees care about and trust one another.

Leaders demonstrate open and honest communication.

Everyone is accountable for his or her actions.

While many organizations have a vision statement like this on the wall, these leaders made a commitment to make the vision a living thing in the organization by talking the talk — and walking the walk.

Step Two: What

Once the Vision statement was approved and shared throughout the plant, managers and employees embarked on a series of dialogue sessions. Using a Culture Transformation Model, they identified which concerns and issues were contributing to the “We-They” divide between management and employees.

The concerns were prioritized and plans of action were developed. Step Two included and emphasized leaders addressing the culture factors of accountability (by developing a plan) and collaboration (by holding frequent dialogue sessions with employees).

Step Three: How

Ultimately, the implementation is at the core of the culture transformation process. Where many approaches are rooted in the belief that employees lack self-motivation and therefore require extrinsic motivation tools (e.g., “carrots and sticks”) to motivate change — this process took a different approach.

In the discovery process, employees repeatedly explained that their disengagement or detachment issues stemmed from a perception that management was distancing itself from the group by:

- Micromanaging

- Not keeping employees informed of company activities, financial and otherwise

- Not allowing employees input into decisions, yet holding them accountable for the results

- Showing no respect, recognition, or appreciation

- Not empowering employees to make positive changes

- Showing a visible lack of faith and trust in employees’ commitment and abilities

- Rewarding employees with meaningless tokens, which they found insulting

Therefore, the management team committed to adopting a new Relationship-Centered Leadership approach grounded in Self-Determination Theory.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

The management team decided to use SDT as its boilerplate model for increased employee engagement.

After an in-depth review of the SDT model, managers could see that motivation was the key to employee engagement. In addition, they began to understand the difference between viewing motivation from a quantity perspective and how to recognize it from a quality perspective.

SDT consists of three core psychological needs:

Autonomy: Concerns the experience of acting with a sense of volition, choice, and self-determination.

Relatedness, or interpersonal connectedness: The experience of having satisfying, social, and supportive relationships

Competence: The sense and feeling of competence at what one does. This also involves the belief that one has the ability to influence important outcomes.

These three needs have been found to correspond with behavioral engagement, which is directly linked to higher levels of commitment, performance, persistence, initiative, and creativity. By framing, linking, and designing employee interactions and work procedures within the framework of SDT’s needs and the organization’s values and vision, the managers were able to demonstrate commitment and influence the attitudes, behavior, and motivation of their employees.

Culture change, at its root, is intimately tied to individual change. Unless mangers are willing to commit to personal change, the organization’s culture will remain resistant and frozen. The plant managers were trained and supported, and senior leaders role modeled, a new way of interacting. They developed questions to evaluate their daily interactions. Sample questions that guided the interactions of managers and employees:

Are we permitting and encouraging employee autonomy?

Will this approach improve and build our relationships with employees, or distance us?

Are we recognizing, developing, and empowering our employees’ competencies?

Are our interactions guided by the values of our vision?

Results: Culture Change

The project was highly successful. Engagement increased, as did quality and safety. The plant became a positive place to work.

Engagement

In 2006, over 60% of employees were described as “detached.” As the culture initiative was implemented, the rate of detached employees began to consistently decrease, hitting a low of 5% in the 2012 survey. This is a 91.6% decrease.

The graph to the right, “Detached Employees.” displays the level of disengagement as assessed by employee surveys from 2006 through 2012.

Quality

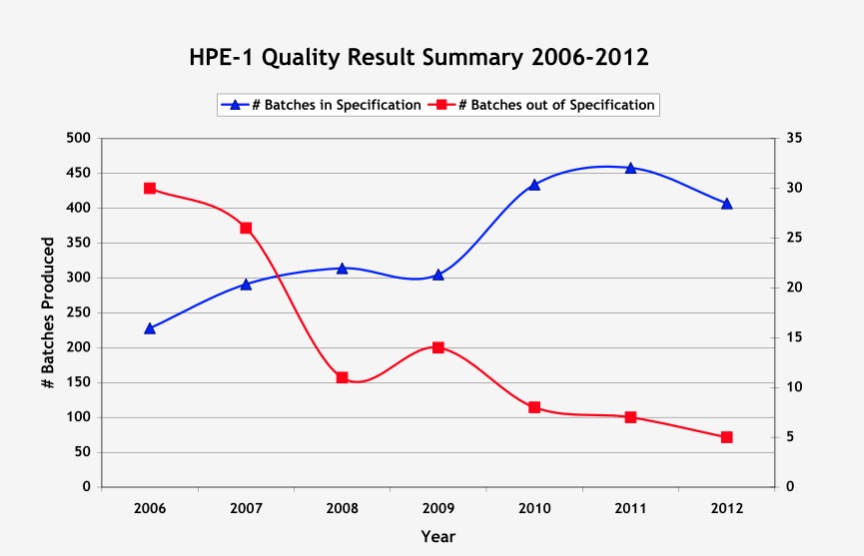

As the employee engagement improved, employee performance and quality also improved dramatically. The number of manufactured batches meeting specifications increased, creating a positive impact on customer satisfaction and a reduction of production costs. As shown in the graph below, “in Specification” numbers increased, and “out of specification” numbers declined. The improvement of “batches in specification” from approximately 225 to 400 is an a 77.7% improvement; the reduction of “batches out of specification” from approximately 425 to 75 is an 89% improvement. The combined quality improvement is 167%.

Safety

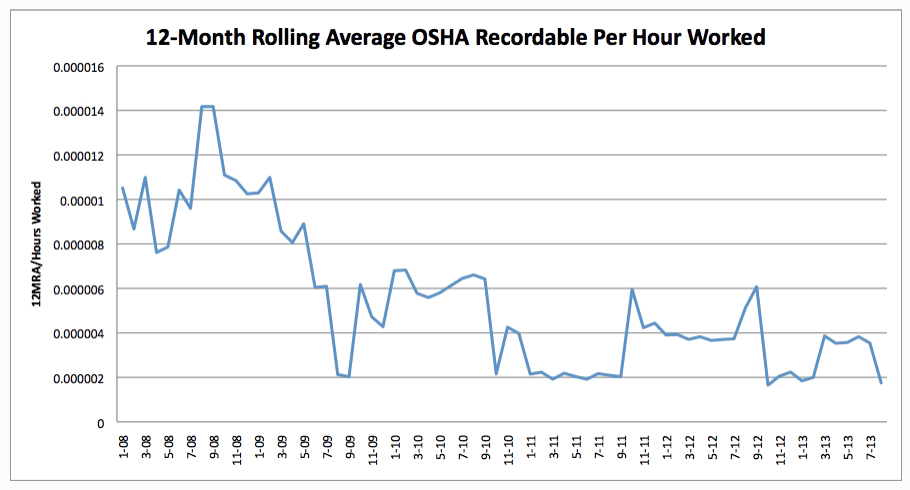

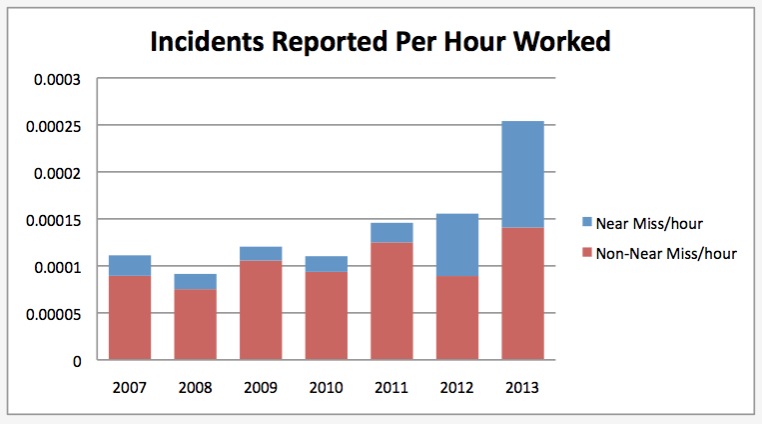

Serious safety incidents are monitored by OSHA, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration; the plant tracks these incidents against the number of person-hours worked. Near the start of the culture change initiative, the monthly average rate varied around 0.00012 per hour worked. At the end of the culture change process, the rate was down to .000002/hour — an 83% improvement.

As shown in the following graph, there is a consistent decline in OSHA recordables with only minor fluctuations. This trend mirrors the positive progression in employee engagement. As the changes in the culture took hold and more employees transitioned to feelings of engagement, the number of OSHA recordables also declined.

Another significant indicator of the link between employee engagement and safety is the reporting of “near-misses,” safety risks that could easily become dangerous. When there is a culture of mistrust, and when managers use punitive actions are used as a means of “reinforcement and motivation,” near-miss reporting tends to be viewed as a “got-cha” by employees, and they under-report.

The following graph shows how many hours passed without a “near miss” (in red) improving over time — and the reporting of “near miss” incidents (in blue) increasing. Coupled with the decline in actual incidents (above), the blue increase represents a growing level of openness and honesty.

The last graph shows that as the culture improved, more employees became engaged, their trust in management increased, and therefore their willingness to report near-misses also increased.

Summary

Changing organizational culture is a difficult and complex task. Most organizations prefer to stay on the tip of the iceberg and attempt to spark change by installing programs or motivating with carrots and sticks.

These superficial approaches are doomed unless leaders are willing to explore the heart of the iceberg — because this is where true drivers of culture exist. Here lies an interlocking set of goals, roles, processes, values, communication practices, attitudes, assumptions, and beliefs, all of which will resist half-hearted attempts of change.

These interlocking elements form your employees’ beliefs about their work, relationships and the organization, and these elements will work tirelessly to prevent or subvert any attempt at long-term change. This is why single-fix changes — such as the introduction of teams, or LEAN, or safety programs — may appear to briefly make progress, but eventually the interlocking elements of the organizational culture take over and any attempts at change are inexorably squashed.

Despite the difficulty and complications inherent in organizational culture change, the results and rewards are significant, far-reaching, and sustainable. Leaders who are willing to take their organization into the heart of the iceberg can create the conditions where all members of the organization can find the motivation to positively participate in changing their culture to be in alignment with their aspirations.

The bottom line:

Leaders Don’t Motivate – They Create the Conditions for Self-Motivation

* note: The Organizational Vital Signs model was revised since the original research for this case. See the updated Vital Signs Model here.

- Case: Safety & Quality in Chemical Manufacturing - October 29, 2013

- Trust: The Spiral of Investing (in People!) - December 9, 2008

Thanks Tom. This was a fascinating read. It was interesting to see how the leaders new they needed a different approach and how you enabled them to take the steps to moving ahead with behaviour change – and culture change.

Thank you so much for this efficient and very clear article. It is so obvious to see the numbers witih the theary.

Thank you for sharing this article with the data and correlating factors. It was interesting that reporting of near-misses went up and how it was explained in conjunction with reported incidents.

Great article and approach Tom. Have a look at the ability of companies to translate training into reality to deliver a sustained H&S culture

Thanks Sissel for taking the time to read and comment on the article and you are welcome!

Thank you so much for this incredibly interesting article. It also very much mirrors my own belief , especially what is said about it being pivotal that senior leaders walk the talk.